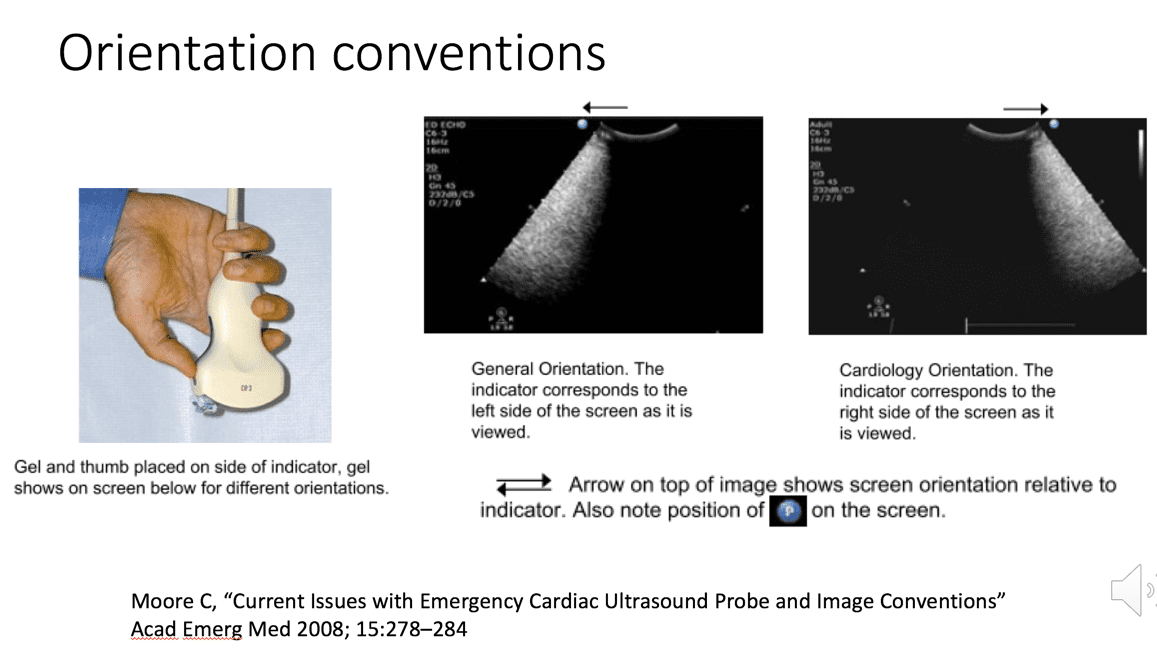

Orientation Conventions

Narration

So this is what I mentioned about the general versus the cardiology orientation. It really is a convention, it’s sort of like driving on one side of the road in the US we drive on the right, in the UK they drive on the left. They are each internally consistent, however there can be issues when the two worlds collide, and we’ll talk about that a bit more in cardiac imaging especially if you’re doing integrated examinations where you’re doing abdominal exams along with the heart. You need to make a choice about whether you’re going to change the convention or stick with a consistent convention and be aware of that. I have an article on this back from 2008 in academic EM that details this and these are where these illustrations are from, but pretty much we’ll be working with the general convention or orientation where the indicator is on the left side of the screen as it is viewed.

Narration

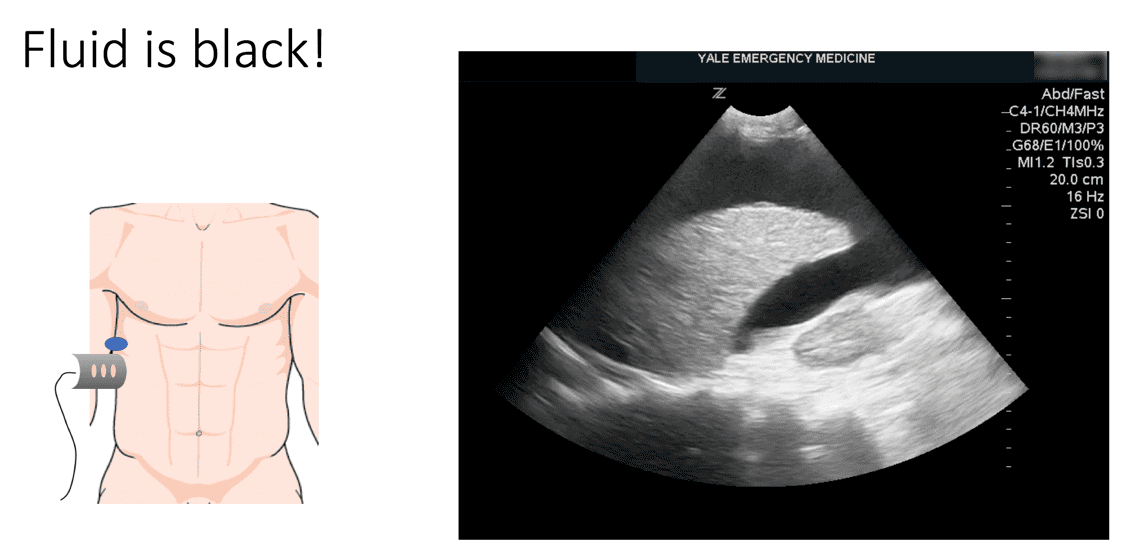

So there’s two basic rules of orientation. The first one seems kind of obvious but I think it’s worth stating, which is that things at the top of the screen are closer to the probe, things that are at the bottom of the screen are therefore further away. The second rule is the one we already talked about which is a convention that the left side of the image as it is viewed is where the indicator is. So depending on where you direct the indicator, that is going to be anatomically where you are looking. This is a classic what we call Morrisons pouch view, it’s a hepatorenal view looking at the liver and the kidney, this view will look for the fast exam when we are looking for fluid. In this case the indicator is directed towards the head, you can see a little of the diaphragm towards the left and don’t worry if you’re not getting these images quite yet, we’ll go through them. Just know in this case the left side of the screen is towards the head, the bottom of the screen is further towards really the patients left side in this case, because that is where the probe is directed. So these are the two rules of orientation.

Narration

I’ll end this segment of the talk with just saying that really remember that fluid is black. On X-rays and CT scans and things like that, black is often air. On US air tends to scatter things, it actually appears bright white. In this case we see a liver, it’s actually a diseased liver, a cirrhotic liver, with lots of fluid all the way around and that’s the black stuff. It’s a bit over-gained, and we’ll talk about gain at some point, but you can still see there’s lots of black fluid surrounding it and that’s the key thing to really look for in point of care ultrasound.

?

v:1 | onAr:0 | onPs:1 | tLb:1 | tLbJs:0uStat: False | db:0 | shouldInvoke:True | pu:False | em: | i: 0 | p: | pv:1 | refreshTime: 1/1/0001 12:00:00 AM | now: 2/12/2026 1:58:00 AM | c: